A Tradition That Causes Pain

“‘A girl who hasn’t been cut won’t get a husband.’ That’s what people used to say,” assured Fatoumata, a 55-year-old grandmother. In a lot of countries, female genital mutilation (FGM/ cutting) is still commonly adopted, claiming that it can ensure the purity and virginity of girls before marriage. Mali is one of the countries. According to UNICEF, 75% of females in Mali under the age of 14 and 89% of females aged 15 to 49 are estimated to have undergone FGM. With donors’ support, Plan International has been working in five villages in Badia, a community in south-western Mali, to fight against this gender-based violence and accomplished some good results.

From March to May 2019, over 50 workshops were held in the five designated villages. Information regarding FGM was delivered to over 600 villagers including men, women, boys and girls. Djaminatou, a 46-year-old lady, has become an educator in her village since Plan International started the project to end cutting of girls in her community.

“Female genital cutting is a violation of children’s rights: the right to physical integrity, the right to good health and the freedom to make your own choices” Diaminatou, 46, says.

Born in 1973, Djaminatou was cut when she was just a little girl. By 1983 Djaminatou’s father decided to eradicate cutting in the family after witnessing his niece suffering from complications after the excision. When Djaminatou was young, she teased her uncut younger sisters, calling them “Blagoro” which means improper girls. It was till Djaminatou had her pregnanciesthen she understood the harm brought by genital cutting. Two out of Djaminatou’s three deliveries were rough and ended up as caesarean sections. Heartbreakingly, Djaminatou lost both babies. Despite having one healthy daughter, that fact that she cannot have any more children still aches her heart.

Djaminatou now believes female genital cutting is a harmful practice and a violation of children’s right. Therefore, when Plan International started the anti-FGM project in her village, she immediately supported the initiative. She also believes the ultimate solution is to pass a legislation that outlaws the practice. “Then, and only then, will we be able to put an end to FGM. But it will take a lot of lobbying and advocating, at all levels: in the government, in the parliament, and in the villages and communities,” Djaminatou emphasized.

Aminata, Djaminatou’s 97-year-old grandmother, brought nearly all of her grandchildren to the cutter but she never thinks genital cutting is the cause of the health problems the children later faced in their lives. Instead, she thinks it was witchcraft that caused the health issues.

Now, Djaminatou focuses on educating the people in her community. “At last, I know what is wrong with me!” is what she typically hears after an information meeting. Women undergone FGM might have problems urinating or experience pain during intercourse. The information campaigns give these women a chance to figure out what has happened to their bodies.

To facilitate the spread of the anti-FGM message, Plan International also requested support from the village leaders who have authority in the aspect of religions or traditions in the community. In Mali, over 90 per cent of the population is Muslims. Men, especially the Imams, are the hierarch in the villages.

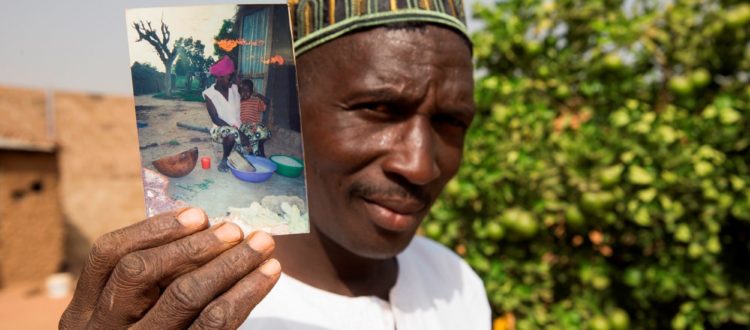

“I had one daughter, a wonderful girl,” Imam Nega Sacko, 48, says.

Nega Sacko, 48-year-old, is the Imam of his village. He always carries the birth certificate and the photo of a toddler with him. The toddler is his daughter. He carries the photo around not only because of his love as a father, but also because he lost his daughter to FGM. The birth certificate and the photo are the only means for him to remind his daughter’s face.

Nega never wanted his daughter to be cut, but one day his “mother” (not his biological mother, but another wife of his father) took his daughter to a neighbouring village. When his daughter was brought back home, it was found she was undergone FGM. Her wound was vicious and there was no way to stop the bleeding. The devastated father can never forget the fear and anger he felt on that day. The poor girl’s wound continuously bled for three days until she passed away. When Plan arrived at Nega’s village to initiate the anti-FGM campaign, he did not hesitate to join so as to ensurethe tragedy he encountered would not happen to anyone again.

In order to make religious leaders like Nega Sacko, Plan International has established village committees, also known as the community-based organisations (CBO), in the five villages. Capacity building session was given to 25 CBO members, five per village. The themes focused on the consequences of FGM excision especially the complications such as haemorrhage, excruciating pain, anemia and cardiac arrest. Topics such as the history of FGM, children rights, and gender-based violence were also discussed. Trained members are required to draft action plans for future activities related to the campaigns and help disseminate information about FGM.

“Everyone in the village has heard my story as people are spreading it around,” says the Imam.

The Imam discusses the consequences of FGM in the mosque with the men from the village, the imams from other villages, as well as his colleagues. It is vital to include men in the process of anti-FGM because men are considered the reason why parents would want their daughters to go through the excision. In Mali, the marriage can be turned down if the girl is found uncut since she cannot ‘prove her virginity’. To ensure that their daughters can find a husband, parents will enforce FGM on their daughters and celebrate the day as if it is the wedding ceremony.

Nega believes men in his village would soon change their minds if they had a better idea of the consequences and history of FGM. He mentioned that the assistant Imam that works with him in the mosque confided in him, “If I didn’t know your story, I would have still been preaching in the name of our religion that the tradition of cutting should be continued.”

The first phase of the project is running smooth and the result is motivating. By the end of May, four out of the five designated villages, which include Makana Brigo, Boro, Golobladji and Gontan have signed the agreement to abandon the practice of female mutilation. The CBO president from Golobladji also changed her mind and decided not to mutilate her four daughters. Plan International aims at benefiting more than 4,600 inhabitants by the end of the project, including more than 2,300 men and 2,200 women. In the next stage of the project, Plan International will pick some grandparents as models and carry out awareness-building workshops with them. Victims of FGM will also be identified so they will bed with medical support.